Why Free Markets in Africa are Integral to Growth and Levelling Up

Let the intense currents of the market forces reign free!

Market forces consisting of buyers and sellers that range from everyday customers, informal traders, and small and micro-businesses, to large corporations and multinationals (MNCs), generate much of Africa’s growth and employ an overwhelming share of the workforce.

There are industries and hustles of all kinds on this continent that can cater to almost all of your individual needs and whims. And, like the world over, your ability to dabble and participate in these markets is largely guided by your stream and pools of currency.

And this is of no surprise to anyone who studies Africa’s history. Capitalism, driven by that human yearning for riches and a better life, underpin the modern African story.

In Africa, Government is the Problem Not the Solution

To paraphrase President Ronald Reagan, state engagement the continent-over, usually spells failure and mismanagement. On the one hand, corruption is rife everywhere and manifests itself under different guises depending on the national and local context. On the other hand, I still don’t think this changes my conviction in arguing that the government graft, nepotism, rent-seeking and straight-up kleptocratic behaviour embedded in leaders looting taxpayer resources and treating national central banks as their personal checking accounts, are why Africa lags so far behind the rest of the world when it comes to development and financial wealth.

Furthermore, heightened government intervention and provision of services requires more state oversight and supervision. In Africa this means a very bloated bureaucracy in a region where it’s not uncommon for the state and civil service wage bill to account for up to half of government expenditures. For example, in Kenya, total compensation of government workers sat at nearly $7 billion or Sh1.17 trillion in 2023, or a third of total spending for that year.

Billions of dollars annually, that could have been invested in expanding the country’s agricultural, manufacturing and technological capacity squandered away on wages. Better yet, that same money is enough to literally build hundreds of thousands of schools and colleges around the country.

Private industry and free markets are the best antidotes to corruption within an African context. I will elaborate more on the specific details and case studies in later articles, but for now, let’s assess the ideas and principles shaping this doctrine.

Business Serves Households

Somebody once said that the business of business is business. I am inclined to agree. Businesses live and die by profit, or breaking-even at the very least. Competition amongst many other businesses instills financial and management discipline in ways that government and the public sector are shielded from. Compelling companies to provide better products and services for their stakeholders.

In a lot of African countries, private firms answer to the people more often than governments. The profit motive also reduces the breathing space for corruption. Sure, there is financial fraud, but even here, shady businesses are still acting to maximise their own interests and growth, sometimes at the expense of investors. They’re usually not engaging in self-sabotage as is the case where leaders and government officials of different African nations help themselves to public money so that they can buy a new house or stash it somewhere in a Swiss bank. Embezzlement of this shade is referred to as employee theft in the private sector.

Such a misdeed is enough to warrant immediate dismissal in a business context. And why wouldn’t it be, it is their money and resources that an employee stole. But in the case of government it’s someone else’s money, i.e. the tax paying public.

Privatization and Private Sector Development Delivers Decentralization

Policies that foster private sector growth, therefore allowing for a larger and more diverse economic base, help steer the decentralization of power and production away from the government to countless industries that are home to even more firms and traders.

This reality is best exemplified by the growing ranks of businesspeople entering into politics throughout Africa. Kenya’s current and previous three presidents operated or ran multimillion dollar businesses at one point or another.

South African President Cyril Ramaphosa (who started out as a trade union leader), is also a wealthy businessman. At one point, he owned a major stake in the Shanduka Group. The company owned stakes in a wide-range of firms in energy, telecoms and financial services, like MTN. With Ramaphosa selling his stake in the group for somewhere in the region of $200-$300 million in 2015.

In 2018, Chinese ecommerce billionaire Jack Ma made headlines by launching Africa’s Business Heroes, a TV show that awards pitch-winning African businesses with grants and other forms of business support and assistance. He was recently appointed as a Visiting Professor at the African Leadership University, a college founded by Ghanaian social entrepreneur Fred Swaniker with the aim of developing 3 million entrepreneurs.

A fast growing, far-reaching contingent of business professionals has formed across the continent, as well as overseas in the African Diaspora. Supplying African governments with fresh blood and new perspectives, along with in-depth management expertise, all the while representing a bridge between commerce and government.

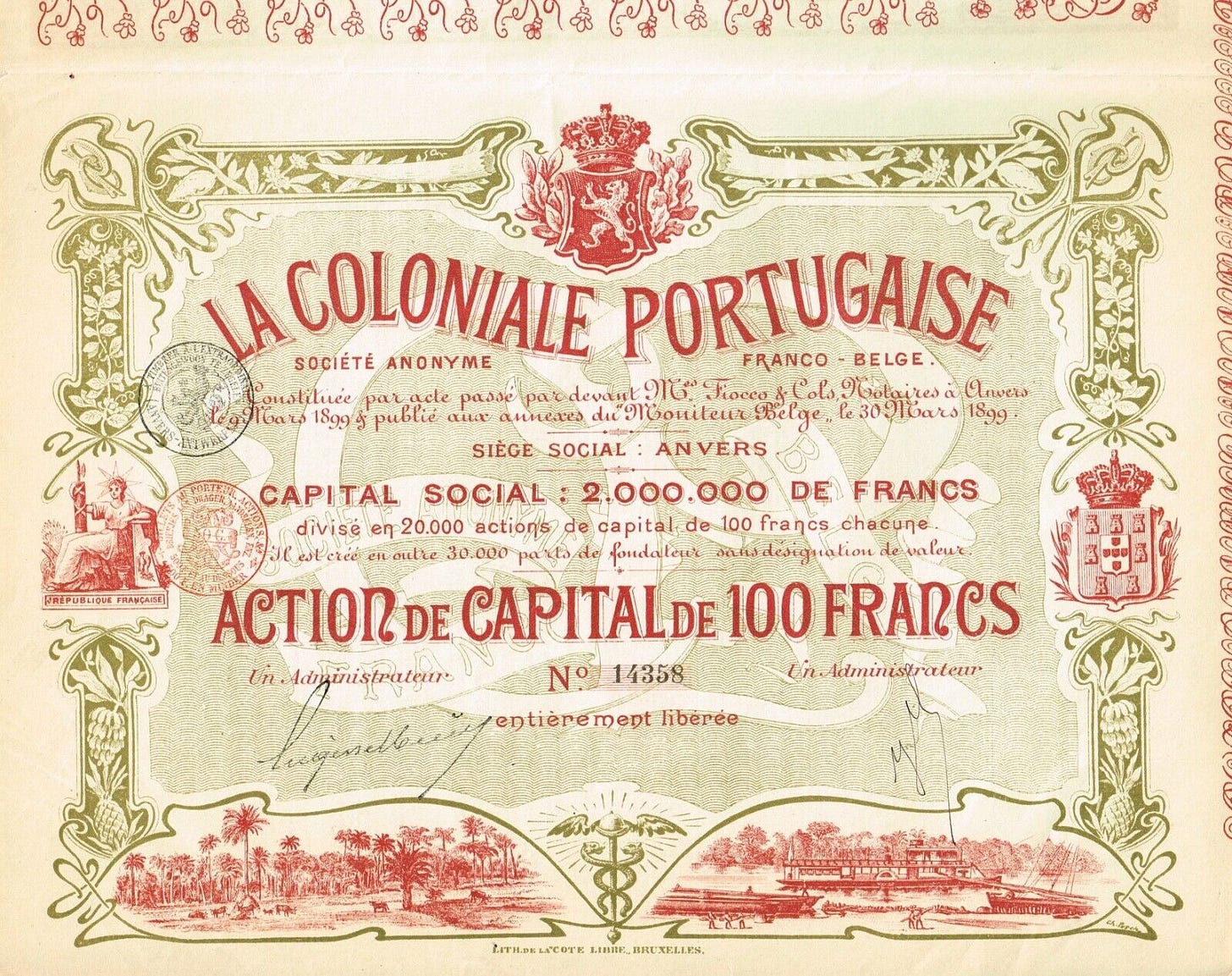

The Chartered Company: A Prelude to the Scramble for Africa

An often overlooked fact is that Africa as we know it today - an intimidating landmass comprising of 54 mostly Anglophone, Francophone and Lusophone (Portuguese speaking) nations - started off with a collection of loosely affiliated enterprises. Beginning with the Casa da Guiné (later renamed Casa da Guiné e Mina), or the Portuguese Guinea Company.

While the Portuguese were not the first outside of Africa to pay a visit, with earlier forays made by explorers like Chinese Mariner Zhèng Hé (郑和) a few decades prior in the early 15th Century, they were at the forefront of discovering and creating new markets for trade between Africa and the rest of the world.

The Portuguese Guinea company was formed in the mid 1400s by royal charter degree, with the intention of exploring and exploiting West African markets for slave labour and tapping into valuable mineral reserves and animal product like gold and ivory.

As a chartered company, the Portuguese Guinea received the permission of the Royal Portuguese government to conduct in commercial trade across Africa on behalf of the country. For all intents and purposes, despite its description and appearance of state influence and control, chartered companies were essentially an early inception of the modern private, incorporated firm. Reinforced by the fact that Portuguese Guinea had the power to issue and sale shares beyond government as a means to raising seed capital.

For chartered companies, such an arrangement was usually sweetened by states awarding them with exclusive monopoly rights. In practice, this meant they could trade in certain parts of Africa with the protection and assurance of their countries’ naval and military forces, uninterrupted and sectioned off from rival competitors like the British, Danes and Spanish at the time.

Private Countries Turned Colonial Profit Centres

What started out as an instrument for state-sanctioned and joint-venture funded expeditions, spawned off the world’s first transnational corporations. The VOC, or the Dutch East India Company and the Virginia Company of London are among the more well-known of them, but others also emerged, such as the Royal African Company, the Royal Niger Company, the Imperial British East Africa Company, the German East Africa company and the British South Africa Company.

Taken as a whole, such chartered firms pursued profit in the trade of people and resources, and inadvertently set-off the race to the drawing up of a post-1884 Berlin Conference Africa. An Africa where the likes of Otto von Bismarck, Henry Stanford and a host of other European colonialists and imperialists carved out the territorial make-up that has come to define the continent ever since.

Colonial powers drew the map of Africa on the basis of efficiently accessing and exploiting its valuable minerals, labour and trading ports. Thus, a continent consisting of many separate and distinctive kingdoms, and indigeneous empires was no more, they were now re-conceived and managed as colonial profit centres.

For instance, warring and conflicting ethnic tribes such as the Hausa-Fulani, Yoruba and Igbo, whose tensions go hundreds of years back into the past, prior to colonialism, illustrates the indifference of colonialists well. The Oyo Empire extensively raided for and traded in slaves among their own and other Africans for nearly 200 years. All of the aforementioned eventually found themselves having to live and govern over each other in a West African country named after the Niger River by a British journalist.

Modern Africa was crafted and shaped to maximise commercial interests. Capitalism and commerce brought this continent together, and I would argue that it’s practically the only thing keeping the continent together and pushing it forward. Africans everywhere are known to possess an entrepreneurial spirit. Salaried workers constitute as a tiny share of all workers across the continent. Almost everyone works for themselves in Africa - it’s high time that African leadership fully embrace private enterprise and become a walking reflection of the people.